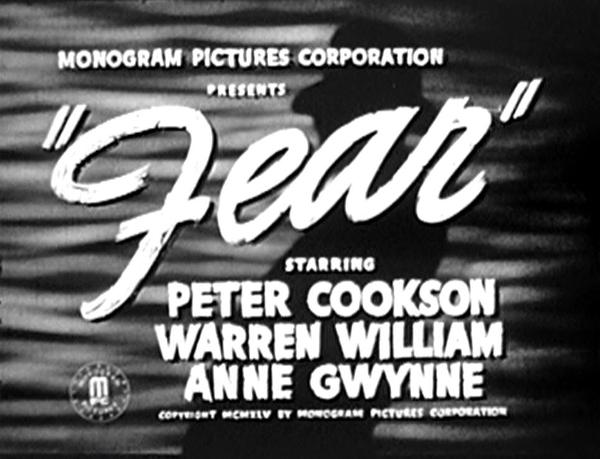

Warren William’s Captain Burke in Monogram’s Fear (1946) is Poverty Row’s version of Dostoevsky’s Porfiry on Raskolnikov’s trail. Peter Cookson stars in the Raskolnikov role, here dubbed Larry Crain. While director Alfred Zeisler is also co-credited for the original story and screenplay, Fear is the Americanized and modernized low budget adaptation of the literary classic Crime and Punishment.

This retelling of the story finishes with a disappointing ending that reduces William’s entire part to a figment of Cookson’s imagination. Notwithstanding the importance of dreams to the source material, this was unnecessary. This final twist will also ring all too familiar to fans of Fritz Lang’s The Woman in the Window (1944), a film originally released nearly a year and a half ahead of Fear.

Cookson, soon to star on Broadway in the original production of The Heiress, is top billed in Fear as down-and-out student Larry Crain. Larry not only faces a $400 bill for fall tuition, but can’t even manage to scrape together the funds to keep his landlady in check. Desperate for immediate cash he pays a visit to Professor Stanley, who earns his extra dollars operating an unofficial pawn brokerage that causes students as much distress as relief. The Professor is later described by some of his students as, “no more than a leech or a black beetle.” Larry also overhears one of them mention how the Professor distrusts banks and keeps all of his cash immediately on hand.

We don’t meet Warren William’s Captain Burke until about of third of a way into Fear, after Larry has killed the pawnbroker.

For the actor who originated Perry Mason on screen and carved a niche playing other movie detectives from Philo Vance to The Lone Wolf, William portrays perhaps his most realistic detective in this low budgeter near the end of his career. His Burke is sly yet amiable as he strokes Larry’s ego, gathering information while making Larry feel more like a peer or a friend than a murder suspect.

Larry instead directs his hostilities towards Burke’s lead detective, Schaefer (Nestor Paiva), who tails him throughout town until Larry decides to go over his head, demanding to see Captain Burke. When Schaefer tells him Burke is busy, Larry confidently declares, “He’ll see me.”

While Fear does an excellent job in focusing on Larry’s mounting guilt and, yes, fear, it glosses over the character’s feelings of superiority, limiting them to the article he wrote about men who are above the law and the conversation he has with Burke after the Captain has read the article. Larry does make his position clear to Burke and Burke does suspect that Larry believes he is himself one of these superior men he’s made reference to. But for viewers who are unfamiliar with the source material these ideas of superiority don’t make much of an impression in Fear, where financial need otherwise plays as sole motivation to Larry’s crime and subsequent guilt.

Also underdeveloped in Fear is the Sonia character, here called Eileen and played by pin-up queen Anne Gwynne. Eileen’s difficulties don’t reach much further than being sixty cents short on a meal that Larry winds up paying for. After that she lands work tending bar and falls for Larry. The character doesn’t play a necessary part in this telling of the story.

Perhaps the oddest aspect overlooked in Fear does not come from Dostoevsky but current events of the day. Given the timing of Fear, with production wrapping up only days before America dropped the first of its atomic bombs on Japan, it seems strange that this present day tale makes no reference at all to World War II. Even with the war over by the time of Fear’s March 1946 release this is a movie where it isn’t even mentioned in the background. It felt like a missed opportunity, especially in a movie completely built around the angst of a young man who was fighting age.

Bringing the focus back around to Warren William, his few scenes only get better as Fear progresses. He brings Larry close to cracking by recreating the murder in the victim’s apartment, leaving the sweaty young suspect to comment, “That’s a very interesting theory,” after watching Burke act out his every move from the night of the murder.

“Let’s go down to headquarters. I’ll show you some interesting facts,” Burke says.

Once they arrive Burke shows Larry some of the evidence that has been collected, including some fibers of clothing, before impressively recalling in intricate detail Larry’s odd clothing from their first meeting. “Stop playing cat and mouse,” Larry demands.

Burke points to the next room and remarks, “They’re busy in there dissecting Professor Stanley’s remains.” His voice rises, almost gleefully, as he invites Larry to have a look, “You’re a medical student, you’ve seen bodies carved up before.”

Later, when it appears Larry is ready to confess Burke gives him reason not to. But that doesn’t mean that Burke is convinced of Larry’s innocence. As Burke heads towards the door Larry asks if he wants him to come with him. He assumes he has been caught. “You want to talk I’ll be in my office at 2:30,” Burke says. He pauses at the door, adding a line that makes clear his feelings about the case: “I’ll be expecting you.”

With The Lone Wolf and his Columbia contract behind him Warren William wasn’t working much during this period. William biographer John Stangeland mentions rumors of Warren’s already failing health prevented the major studios from taking the chance of losing time or money on him.

Warren played in the Edgar G. Ulmer cult classic Strange Illusion for PRC about a year prior to Fear. Stangeland writes, “during most of 1945, Warren was continuing to battle fatigue, respiratory infections and a general pain in his limbs” (197). He’d only appear in one final movie after Fear, The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1947), but remained busy during the period in between through his involvement in the Strange Wills radio program.

Warren’s ingratiating and natural performance in Fear provides yet another late reminder to the shame of his career being cut short by his illness and premature death. While ‘40s roles in movies such as Arizona (1940) and Wild Bill Hickok Rides (1942) show that Warren could still effectively wear a black hat, Fear provides evidence that he could have handled a wider range of dramatic supporting roles had his career continued.

Another great review article; thanks, Cliff!

Thanks, Jeffers! It’s an interesting title, I’m glad TCM played it at a time when many people could actually watch.

Great job as always, Cliff. As cheap as “Fear” is, it’s very instructive to watch Warren in it – he’s exponentially better than everyone around him, but he’s still having FUN. He refuses to phone it in, and he gives a nice performance with what little screen time he has. I first saw this without the “just-a-dream” ending – the other version ends abruptly when Larry is killed walking across the street, a hollow moral comeuppance if ever there was one.

Keep up the great work!

-J

Hey John,

Just spotted your comment tonight when I came over to do a little tinkering to the site–sorry about that.

Interesting that you saw it with a different ending than I did–I actually didn’t know that such a version was available. Do you think they released it that way or did a TV station trim if off somewhere down the line?

Not a very happy ending for you then, huh? But at least it legitimizes Warren’s part in the movie!

Hope you’re well, my friend!

Cliff

So glad to learn about “the other profile.” Fine, fine actor & so handsome. Seeing those two movies back to back (1935 vs. 1946) initially made me think that like John Barrymore, he too led a dissolute life & died from alcoholism. Not so, but equally sad.

Hope you enjoyed the movie, Winifred! Right, by all indications our man Warren was a homebody, who lived a sober, happy life with his hobbies, his dogs, and his beloved wife.